Henri Astier y livre sa lecture des livres de Fourest, Schneidermann, Todd et Federbusch consacré à "Charlie".

Ci après le passage sur la Marche des Lemmings, que nous ne vous traduirons pas pour vous forcer à faire un peu d'efforts ! Sky my Lemming !

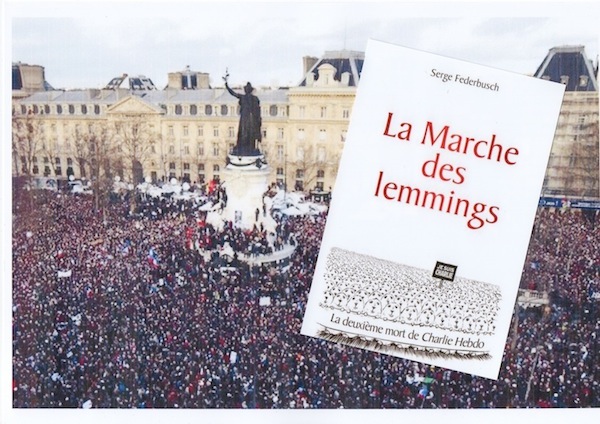

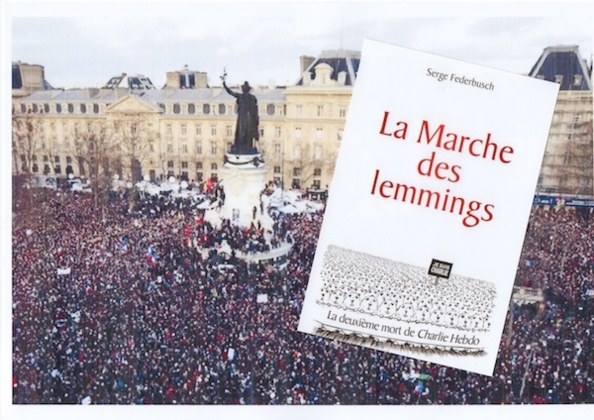

"Serge Federbusch attacks the movement from a different but equally original perspective. He is a libertarian conservative - a rare breed in France, which makes his book, La Marche des lemmings, all the more intriguing. He starts by criticising Charlie Hebdo itself, noting that its mix of anticlericalism and bawdiness had become become profoundly uncool. Cartoons of Pope Benedict sodomising a baby or the Virgin Mary raped by the Wise Men had lost their shock value. Only when Islam was targeted could the magazine reliably offend. With the Muhammad cartoons, Federbusch suggests, it was courting controversy in an attempt to recapture its lost mystique.

Some of the charges are overdone. He puts the worst possible interpretation on the official response, accusing President François Hollande of jumping on the Charlie bandwagon to shore up his popularity and divert attention from security failures. Equally uncharitably, Federbusch regards the marchers' unwillingness to name the enemy as radical Islam, and their focus on safe, far-right villains, as cowardice. He likens them to lemmings seeking safety in numbers rather than confront danger, neglecting what can just as easily be seen as a genuine desire to send an inclusive message.

Federbusch is at his most persuasive when he exposes some dubious upholders of liberty. This includes a government that helps keep newspapers afloat with subsidies worth about €1bn a year in the name of "the independence of the press". Despite its freewheeling pose, Charlie Hebdo was a ward of the state. Shortly before the attack, its owners had gone cap in hand to the Elysée Palace to secure extra help. The fact that few commentators saw anything odd about Mr Hollande joining the marchers to beat the drum of "free expression" highlights the cozy relationship between French officials and journalists.

But a press dependent on state handouts is not the only threat to freedom. Just as the government was defending Charlie Hebdo's right to be outrageous, it was denying that right to the paper's critics. Dieudonné, an anti-Semitic comedian, received a two-month suspended sentence for a bad joke suggesting solidarity with one of the Paris killers. In the weeks after the attack, about 100 people were prosecuted under the vague charge of "incitement to terrorism". Many got custodial sentences of up to four years over drunken outbursts during run-ins with police ("Your Paris colleagues got what they deserved", "Allahu Akbar, screw France, Arabs are here.") Some were jailed for saying similar things on social media. School-age "apologists for terror", including one as young as eight years old, were questioned by police.

As Federbusch notes, "for years the general climate has been unfavourable to free expression in France - a trend abetted by the organizers of the 11 January march". All of them support Draconian incitement and discrimination laws that amount to bans on certain forms of idiocy. A liberal society should allow bigots to discredit themselves in open debate, but no one is making that point in France. It is a country where someone who wrote on Facebook "Les Ruritaniens sont des salauds" could be fined up to 12,000 euros for "public insult" (if Ruritanians existed). As long as such laws remain on the books, the Charlie movement will be remembered as a touching but ultimately hollow show of sympathy."

Ci après le passage sur la Marche des Lemmings, que nous ne vous traduirons pas pour vous forcer à faire un peu d'efforts ! Sky my Lemming !

"Serge Federbusch attacks the movement from a different but equally original perspective. He is a libertarian conservative - a rare breed in France, which makes his book, La Marche des lemmings, all the more intriguing. He starts by criticising Charlie Hebdo itself, noting that its mix of anticlericalism and bawdiness had become become profoundly uncool. Cartoons of Pope Benedict sodomising a baby or the Virgin Mary raped by the Wise Men had lost their shock value. Only when Islam was targeted could the magazine reliably offend. With the Muhammad cartoons, Federbusch suggests, it was courting controversy in an attempt to recapture its lost mystique.

Some of the charges are overdone. He puts the worst possible interpretation on the official response, accusing President François Hollande of jumping on the Charlie bandwagon to shore up his popularity and divert attention from security failures. Equally uncharitably, Federbusch regards the marchers' unwillingness to name the enemy as radical Islam, and their focus on safe, far-right villains, as cowardice. He likens them to lemmings seeking safety in numbers rather than confront danger, neglecting what can just as easily be seen as a genuine desire to send an inclusive message.

Federbusch is at his most persuasive when he exposes some dubious upholders of liberty. This includes a government that helps keep newspapers afloat with subsidies worth about €1bn a year in the name of "the independence of the press". Despite its freewheeling pose, Charlie Hebdo was a ward of the state. Shortly before the attack, its owners had gone cap in hand to the Elysée Palace to secure extra help. The fact that few commentators saw anything odd about Mr Hollande joining the marchers to beat the drum of "free expression" highlights the cozy relationship between French officials and journalists.

But a press dependent on state handouts is not the only threat to freedom. Just as the government was defending Charlie Hebdo's right to be outrageous, it was denying that right to the paper's critics. Dieudonné, an anti-Semitic comedian, received a two-month suspended sentence for a bad joke suggesting solidarity with one of the Paris killers. In the weeks after the attack, about 100 people were prosecuted under the vague charge of "incitement to terrorism". Many got custodial sentences of up to four years over drunken outbursts during run-ins with police ("Your Paris colleagues got what they deserved", "Allahu Akbar, screw France, Arabs are here.") Some were jailed for saying similar things on social media. School-age "apologists for terror", including one as young as eight years old, were questioned by police.

As Federbusch notes, "for years the general climate has been unfavourable to free expression in France - a trend abetted by the organizers of the 11 January march". All of them support Draconian incitement and discrimination laws that amount to bans on certain forms of idiocy. A liberal society should allow bigots to discredit themselves in open debate, but no one is making that point in France. It is a country where someone who wrote on Facebook "Les Ruritaniens sont des salauds" could be fined up to 12,000 euros for "public insult" (if Ruritanians existed). As long as such laws remain on the books, the Charlie movement will be remembered as a touching but ultimately hollow show of sympathy."